Tactical Test-Taking Strategies

Lessons learned from taking thousands of multiple choice questions.

Med school is all test after test after test, and so a little over a year into it and I’m noticing some patterns. Here are simple strategies that brought order to chaos. While most of this is from med-school tests, the principles apply to nearly all multiple choice exams.

Practice questions

Only through practice on questions will you improve your technique, accuracy, endurance, and learn what’s important. Do not passively read your review books and notes. Question banks are the most effective and efficient study method.

You should jump into doing questions before you feel ready. If you wait until you feel ready, you’re too late. Questions sharpen contrasts, a key part of learning to differentiate diseases and disorders. Don’t wait until you’ve reviewed to start questions; consider the questions and working through the explanations as part of the learning process. There is only one score that matters: what you get on the exam. Practice problem scores don’t count for anything. In fact, you probably remember better after the small emotional jolt of getting the answer wrong. I find that if I guess correctly, I’m relieved and may not pay as close attention to the explanation versus if I had gotten the answer wrong. If you’re learning, you’re headed in the right direction.

Reviewing and accumulating all the random facts is just part of studying for an exam; another big part is learning how to make sense of all those facts and how they relate, an experience that you only get from working through questions that put these random facts in context and draw contrasts.

Read slowly. Don’t just read and nod along but parse the meaning of each and every single sentence. Make sure you understand each step of the pathophysiology or mechanism of action. Even take the time to parse out each syllable in long words. In medicine and science, a lot of meaning is packed into each syllable of words like choledocolithiasis. This may all feel slow, but it’s reinforcing neural pathways and ultimately to speed up your future reading comprehension. Seek to understand on the first pass. If you go fast, you’ll cheat yourself and likely end up re-reading the material anyway. If you’re reading fast to cram more in to your study time, consider simply budgeting more study time. Take a shorter lunch break. First gain accuracy, then gain speed.

Pay attention. There are two types of questions you miss. First, there are those where you simply don’t know the facts needed, so you guess intelligently. Second, and likely the majority of questions I miss, the ones where I misread the question. I either skimmed quickly past a phrase or I didn’t understand the significance of some fact. These are the ones where you’re reading the explanation and smack your forehead. This goes along with “Read slowly”: parse every piece of data for its significance. There are no wasted words in high quality question banks.

Emotional reactions have a lasting effect on memory. Wrestling with a question and the immediate emotional and intellectual feedback of seeing the answer helps solidify the knowledge. It’s important that you commit to an answer so you increase the emotional charge in the event you’re wrong. Giving up and guessing is less emotional; it’s better to convince yourself of one answer, commit, and click submit. One trap I stumbled into is that even when I got a question right but just barely, I found I got sloppy in reading through the explanation. In many cases it would have been better had I got the answer wrong to grab my attention and drive me to achieve understanding.

Commit to an answer before looking anything up. I often find myself wanting to look up a fact in the textbook before clicking submit, but that lessens the emotional payoff. It’s better to think of what specific information you want to look up and how that factors into the answer choices. That way, when you do get to see the explanation, you really drive home the critical details you were missing. It’s best to commit to an answer, let the chips fall, and use that energy to understand the correct answer. Don’t worry about getting a low score from wrong answers: the only score that matters is the real exam.

There’s some evidence that if you take a pretest before you’ve even been exposed to material, you’ll do better when it comes to the actual test afterward. If your scores are not improving or you are just guessing, you might not be ready. Consider stepping back to review more.

Drilling on questions also helps you understand your own psychology. Recognize the signs that you’re tiring or getting sloppy, and learn to refocus. Recognize your proclivities to jump toward certain answers and not read the question fully. One odd thing I noticed is that, for questions where two answers are very close, I tended to prefer the first of the two. Once I recognized this tendency, I started catching myself and instead focus on those choices without bias. If you’re consistently choosing the second best answer, ask yourself what is it that distracted you or tipped you the wrong way? Are you over-thinking the question, ie. adding unnecessary “logical” steps to justify the wrong answer? Critically investigate what you are missing and where you went off track.

Doing more questions can also perpetuate bad habits. If you stop improving or regress in performance, it’s a sign you’re developing sloppy habits like not reading the entire question or not paying attention to every lab value mentioned. Investigate why you’re choosing wrong answers to see a pattern emerges.

Mark questions valuable to see again. Doing an entire question bank again from scratch is probably not the best use of your time, but some questions teach valuable lessons and are worth returning to down the road. Flag/mark such questions for later studies. But be sure to get everything you can out of the explanation in the moment. Don’t mark a question telling yourself you’ll come back to study it later. There never is a “later” as the pace of life only picks up.

Start easy. Consider doing a test with all easy questions so you can start easing into concepts and get some positive vibes going. However, don’t be fooled into thinking this is your actual performance until you’ve cut your teeth on some harder questions.

Practice until these techniques are second nature and you’ve killed bad habits. Techniques will only incrementally improve your performance. There are no true shortcuts on these exams and these techniques only work when you already have the core knowledge.

First sentence, last sentence

Read the first sentence and then the last sentence. Skip everything in between for the moment. Skim the answer choices. Now you’ve got your context. You know what topics are going to be relevant. You know what type of answer is expected. As you go through the rest of the scenario and answer choices, your brain is already working quietly to connect the dots. You’re primed to pay close attention to key information as you continue reading.

At this point, you can skim the answer choices and probably immediately rule out one or two. In some cases, the answer is obvious (but don’t jump until you’ve read everything).

Now go back to read the rest of the scenario and attack the remaining answer choices.

You’ll avoid the situation where you’re reading along thinking you know exactly the diagnosis, only to come to the end and realize the prompt is asking you something different like a side effect of the treatment for that obvious disease (second-order sequence instead of first-order recall). If you had known the prompt, you could have been reading the scenario and already thinking of how to make a connection to the prompt. Wasted time and energy.

If there’s an image, look at it before reading the full question to see if you recognize anything. Often, after only reading the final prompt and glancing at the answer choices, you can already rule out one or more wrong choices in seconds. Classic histology or gram staining is “classic” for a reason.

Study the answer explanations

Always review explanations. First for the correct answer, second for your wrong answer, but also for all the other answers. Specifically look for how you could have ruled out each incorrect answer. The point of the question isn’t just the information limited to the correct choice; the point of the question is the integration and contrasts between all answer choices. A good rule of thumb is that you should spend more time studying the explanation than you just spent completing the question.

Markup your notes/textbook. Find the topic in your notes, underline the most important physical or lab findings, etc. Put a small dot next to the tested fact. Over time, the highly tested material becomes apparent. Not all information is weighted equally, and you’ll soon start to see which topics are most important. Avoid cluttering your notes and only do this for things you got wrong. I used a different dedicated color for each question bank.

Some topics are not that important or not substantial enough to merit their own question, so instead they will be frequently used as distracting (wrong) answers. Becoming familiar with these secondary distracting topics is as important as familiarity with primary tested topics. Don’t skimp on studying wrong answers.

How do you know when you’re read to move on to the next question? Ask yourself: If I saw this again, would I be able to rule out all the wrong answers?

Review topics, not isolated details. If you get a question wrong, don’t just memorize the specific fact you missed. Go and skim over the entire disease or pathway in context. If the answer stems were all a cluster of related diseases, skim those and understand how to compare and contrast. If it was a bone tumor question and the answer was a particular bone cancer, review the specifics of that cancer, but also do a quick recap of the other ones. If the answer was a particular enzyme in the purine salvage pathway, review the entire pathway. Take every opportunity to learn in context.

Record learning points

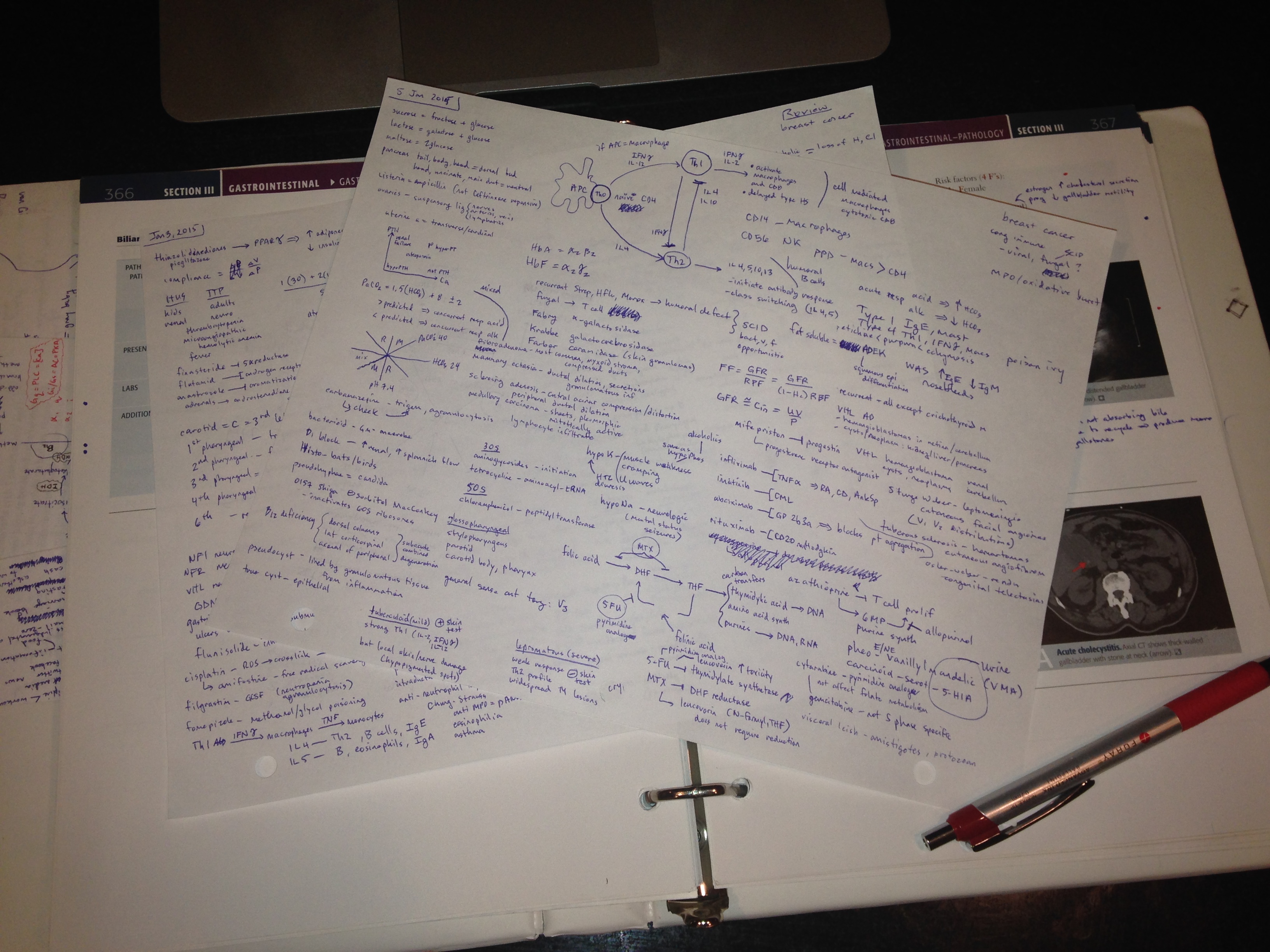

Whenever you have an “Ah, ha!” moment, write it down. Keep this very simple and low-friction. You don’t want to complicate this because you probably will not come back and review. Just the simple act of recording the learning point forces you to synthesize a precise factoid suitable for cerebral storage. If you got a question right but just barely, consider recording the learning point to solidify your thinking. Just as you take notes while you’re studying lectures, treat question banks as study time and take a few simple notes. Don’t waste time making these notes pretty. Every day you start with a new page and blank slate.

Instead of simply stating the correct answer or tested fact, put it in contrast with the wrong answer you picked, eg. differential diagnosis.

This process will seem to slow you down, but it’ll quickly pay dividends as you speed up. As your knowledge base grows you’ll pick up speed because you’ll record fewer learning points and you’ll answer questions faster.

To avoid clutter and save time, avoid writing things you already solidly know. Instead, just let your mind stew on the concept for a moment to reinforce those neurons before moving along.

Read more: MedSchoolTutors: Creating a UWorld Journal

Chief complaint

The first sentence likely contains the most important clue and sets the context. Here are a few classic tip-offs.

- chief complaint - your diagnosis must absolutely explain this

- whatever the patient came in complaining of is the most important thing to address

- race - anytime race is mentioned, it’s a clue

- African-American - HTN, sickle cell, autoimmune

- white - cystic fibrosis, membranous nephropathy

- Greek, Italian - classic Mediterranean patients - B-thalassemia

- sex - female autoimmune

- age - diseases sometimes target a rough age range: childhood, middle age, elderly

- 1-2 yo boy - x-linked

- obese - DM2

- occupation, home environment - environmental exposure

- farmer, veterinarian - animal exposure, hypersensitivity to moldy hay

- construction worker, old apartment, painter - lead poisoning

- college student - Neisseria, mono

- exotic environment

- an emergency department in the third world - think of old drugs not used anymore in the US

- Chloramphenicol causing aplastic anemia (no longer used in US but might encounter in third world)

- an emergency department in the third world - think of old drugs not used anymore in the US

- immigrant or foreigner visiting who recently became ill

- unvaccinated, endemic disease (late manifestations), lack of newborn screening

Beyond Buzzwords

Initially you’ll get really good at recognizing pathognomonic phrases for symptoms. These buzzwords are concise ways of communicating often complicated pathophysiology. But learning buzzwords will only get you so far, and soon you’ll plateau when you hit questions without these classic phrases.

Alternative descriptions. Instead of telling you “patient complains of dyspnea”, the question indirectly describe that the “patient is winded during regular daily activities.” As you do more and more questions, you’ll learn all these alternative descriptions for common findings.

Understand what they’re telling you. To go to the next level, you need to recognize what the question is trying to tell you. You need to categorize multiple physical findings into their underlying pathophysiology so you see through the buzzwords.

Patient presents with history of dyspnea, orthopnea, and ankle swelling.

What that means:

Patient presents with signs of both left-sided heart failure (dyspnea, orthopnea) and right-sided heart failure (ankle swelling).

Ruling out answers

Never commit to an answer without ruling out other choices. This will make sure you’re not just jumping for a distractor. Once you rule out a choice, you can completely forget about it and focus your attention on comparing the remaining choices.

Multiple choice tests are as much about knowing the right answer as being able to rule out all the wrong answers. Sometimes you arrive at the right answer only because you ruled out all the other choices.

A single phrase can rule out an answer choice. The question prompt may mention an ancillary test that was performed whose only purpose is to rule out one specific answer choice.

Patient presents with X, Y, Z that appear to be some form of anemia. In the course of workup, direct Coombs test was negative.

- A

- B

Autoimmune hemolysis- D

Every answer choice was included for a reason. Don’t just rule something out because it simply seems odd. As I got faster, I had the tendency to sometimes rule out answer choices quickly because they seemed unrelated. This was a bad habit because often what seemed immediately unrelated was in fact related in an indirect way. I now force myself to consider what each answer choice means and why it was included before crossing it out. I can catch myself going down this path now: when I’ve ruled out several choices but the remaining choices all seem a muddle. That alerts me to the possibility that I’ve ruled out the correct answer, and so I backtrack a little to reevaluate anything I didn’t carefully consider before crossing it out. If you’re finding that you’re often ruling out the correct answer, you need to slow down and be more sure before ruling things out.

If you’re unsure, skip that choice for a moment and continue evaluating the other choices. Sometimes the other choices will shed light on the one you didn’t immediately understand.

I often found myself picking the second best answer, and this was typically because I was over thinking the question and second guessing the test writers.

Once you’ve narrowed down to two answers, ask yourself “What is different between these choices?” and then look back in the scenario for specific clues.

When faced with an unfamiliar answer choice. Forget about it for the moment, and focus only on the answer choices you do know, the ones that you are capable of ruling out with your knowledge base. Only pick that unfamiliar choice if you can be reasonably confident in ruling out the other choices you know about. Suppose you’ve ruled out all but the unfamiliar and one that is familiar, but you’re uncomfortable with that familiar one. Resist the urge to simply guess the unfamiliar one as a way out; that’s a baseless guess. Think critically about the one you do know and use that as the basis of your decision to rule that known answer in or out. Be careful that you don’t read meaning into the unknown answer, i.e. project onto it what you think it might mean when you truly have no basis.

Practice good habits. Practicing good habits will see your score continue to rise as you accumulate the information and learn better how to apply it. If your score has plateaued, then you need to take a close look at what habits you’re practicing. Don’t rush: start slow to gain accuracy and build execution speed later.

Guessing intelligently

If you have to guess, do so intelligently:

- Rule out as many wrong choices as possible.

- If there are multiple answers that are equivalent and one that is different, then it’s likely the equivalent group is all wrong together.

- If two answers are the opposite of each other, then the answer is likely one of those. Ignore the other choices.

- Use epidemiology to pick the most likely. The most common disease (avoid zebras). An adult patient with no mention of chronic or childhood issues, then rule out congenital diseases that would have shown up in early childhood (e.g. hemophilia, sickle cell). Anything that occurs suddenly without any history, think acquired instead of congenital.

- Avoid costly or invasive diagnostic tests.

- Don’t go for something you’ve never heard of until you’ve ruled out all other options.

Histology

Most histology looks like a mess at first, but you should always start at the center and try to identify what you’re seeing. The “area of interest” will not be on the periphery; it will be near the center. Literally put your finger in the exact center and scan that square centimeter for what is of interest. If you see something funny in the periphery that’s not also found in the center, then ignore it. Ask yourself what you expect to see, eg. the esophagus is nonkeratinized (stratified) squamous epithelium.

Look for characteristic features:

- Eosinophils (bilobed)

- Neutrophils (3-5 lobes)

- Macrophages (large, multiple nuclei)

- Auer rods (acute myelogenous leukemia)

- Granulomatas (pink)

Avoid outliers

When one answer is totally different than the others, it’s likely a distractor.

- Oxygen curve is shifted to the right because of B.

- Oxygen curve is shifted to the right because of C.

- Oxygen curve is shifted to the right because of D.

Oxygen curve is shifted to the left because A.

Boards questions almost always give you enough information to make a diagnosis, and rarely is a patient without risk. So avoid those answer choices:

- The patient is at risk because of X.

The patient has no risk because of Y.Not enough information is provided to make a diagnosis.

Account for every abnormal finding

Your answer needs to explain every given lab value and physical finding. If there’s some seemingly completely unrelated lab value that’s wildly abnormal and you cannot explain it with your answer, then think harder about the other choices. There are no wasted words in a question prompt.

Tunnel vision. This is especially true in disorders involving multiple systems. Individual answer choices may address individual system dysfunctions, but you need to make sure that your chosen answer explains all abnormalities. For example, a patient presents with renal dysfunction, joint pain, and hematologic abnormalities. The individual answer choices might be nephritic syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and myelodysplastic syndrome. Each of those answer choices correspond to a chief complaint, but none answer the whole picture. Be careful not to jump at a single physical finding. If multiple systems are involved, you need to tie as many together as you can. This patient has lupus.

Classic clues

There are some triggers that should either perk your ears to a likely diagnosis or rule out specific answer choices:

- African-American female → autoimmune

- 20-40yo female → autoimmune, multiple sclerosis

- “Patient presents to emergency room…” → unlikely a chronic issue, acute often means vascular

- “Complaining of progressive symptoms for several months” → tumors can develop over months

- Infant or first few weeks of birth → genetic

- no family history → recessive

- female → ignore x-linked

- “multiple rounds of antibiotics” → no gut flora causing Vitamin K deficiency (bleeding), C diff

- medication that was recently prescribed → side effects causing chief complaint

- multiple sexual partners, IV drug use → consider STDs or HIV/AIDS and opportunistic infections

- “Family history of <symptoms/disease>” → this always factors into the diagnosis

- aspiring athlete → anabolic steroid use

Tip offs

Specific constructs can help clue you in to what they’re trying to get at.

- “What is most likely?” - forget about rare diseases, just think what is most prevalent. Avoid zebras. It’s likely more than one answer is possible, but you’re being tested on epidemiological prevalence to determine the most likely.

- “What is the next step in management?” - There might be an overall treatment goal, but this question is likely asking about immediate next steps.

If most of the questions (3-4) have the same base phrase but differ in the second half, look to choose among those if you have to guess.

Patient is having a reaction to heparin.

- Discontinue heparin, do X.

- Discontinue heparin, do Y.

- Discontinue heparin, do Z.

Do something completely different.

Examine the answer choices together. If several choices are equivalent, then they might be ruled out together as a block.

Question, blah, blah, blah.

Decreased pHIncreased hydrogen ion concentrationDecreased bicarbonate- Something else

One answer may refer to a combination of others. Often you can ignore the other choices not involved in that combination. This shows up more so on lower quality tests.

Question, blah, blah, blah.

- Dog

- Cat

Tiger- Dog & Cat

Three types of questions

There are three types of questions: those you know immediately, those you don’t have the knowledge to answer, and those that you’ll end up pondering. Every question is worth the same as every other question, so you can be strategic about how you spend your time and energy.

First calculate your benchmark time per question: test is X minutes with Y questions, so you need to average (X/Y) per question.

For the easy bread-and-butter questions, answer them immediately to lock in the majority of your points.

Some questions you simply won’t have a clue about because you’re lacking the requisite knowledge. It’s a death trap to fritter away your time on these. Narrow it down to 2-3 choices and guess. You want to avoid the situation where you’ve got 10 minutes left but 20 questions, and so you make sloppy mistakes on easy ones.

For these marked questions, go carefully and spend the time. These questions will make the difference between pass and high pass.

Read the entire question carefully.

Your middle school teacher was right. As you’ve gotten used to banging through questions, sometimes a question will seem so easy that you jump right to the answers looking for what you already have in mind. Test-writers know this too and can create a dead obvious question except for one small detail that totally changes. And they know exactly the trap answer to put for those zipping through.

Make sure you’ve taken into consideration every single symptom and avoid the knee jerk choice. The first sentence here sounds like lupus, but reading the entire question guides us to dermatomyositis.

Patient presents with malar rash and signs of chronic inflammation and a positive ANA … Patient also complains of proximal muscle weakness. The ANA shows anti-Jo-1 antibody.

Lupus- Dermatomyositis

I can’t count the number of times I’ve jumped to an answer after reading the first sentence or two only to be wrong. Unless you’re clearly committed to guessing, you better have a reason for ruling out all other answer choices before you click submit. Forcing yourself to address each (incorrect) answer choice in turn will help you squeeze out these sloppy errors.

NBME has released their guidelines for writing questions which go into great detail on how they choose and format their standard exam questions.

Many thanks to my classmates Ming Lee, Erik Reinertsen, Evan McClure, Juan-Manuel Duran, Jason Boulter, and LeslieAnn Kao for discussions.