How to write a systematic review and meta-analysis

Get organized, define your scope, and don't get bogged down.

Reviews are a great way to learn about a topic as a new student but also contribute by bringing clarity when multiple studies cloud the topic. This article talks about getting organized, narrowing your scope, and tips for writing the paper.

Get organized

Organizing and sharing data with collaborators heavily influences the efficiency of your progress. Use Google Docs for real-time collaboration on spreadsheets and comments to keep in sync. Use Mendeley for citations and integrating with Microsoft Word. Zotero has thousand of journal style templates to download for Mendeley. Turn off the feature that pushes your PDFs to the cloud; it’s unnecessary, seems to cause duplication, and this way you’ll always stay within the free pricing tier.

Familiarize yourself with the PRISMA guidelines. Journals now tend to expect that level of rigor and documentation. Hit everything on the checklist.

Create a document for your research notebook. Record every query, date performed, and result counts. Once you’re happy with a query, export the results to a spreadsheet (PubMed and Scopus let you export CSV which imports into Google Spreadsheets). For each row in this spreadsheet of results, you’ll want to have columns annotating how the article was handled at each stage in the PRISMA screening process. There are really three stages you need to document, so you can probably setup three columns: is it a duplicate paper (if combining results from multiple databases), result of reading title/abstract, result of reading full text. Plus a column for free-text notes: variables assessed, outcomes assessed, or why you rejected. Setup formulas that keep counts of each column.

Narrow the scope

If you’re finding a lot of papers attempting to answer a question, then you’re likely on a valuable topic. Look at previous systematic reviews in your target journal: how many articles do they initially screen and how many do they ultimately include? Usually it’s something like 100-500 initially screened to ultimately include 10-20 articles. If your query is returning 1000+ articles, then do yourself a favor and narrow it. This will take some time playing with the query, and be sure to document this evolution in your research notebook document.

Narrow your date range. If you’re looking at complications for a surgical technique, maybe you don’t want to include articles from 1980 when many other factors in a patient’s care were different from today.

Lumpers and splitters. If you’re still overwhelmed by the search results or have multiple questions swirling in your head, look for a way to split up the topic. Aim for the most important question and set aside secondary questions for a separate study. Take notes so you can discuss with your colleagues and come back later.

Quality over quantity. Do not try to include every single article that even tangentially relates to your question because you’ll end up with a lot of poor quality studies that will degrade your findings. Use something like the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to assess for quality. Consider tightening your inclusion criteria in ways that weed out low quality studies, eg. well defined cases/controls, adequate followup, etc. More studies does not mean stronger conclusions; more studies often means more variation, bigger confidence interval, lower p-value.

Avoid getting bogged down

Don’t read into things too much. Not every paper will report on every variable you’re interested in. If the paper doesn’t record an outcome measure that you’re looking for, then move on. You don’t have time to wade through their raw data and make your own interpretations. Only record what they record so you stay unbiased. There’s always a balance, but as much as possible, you need to “delegate” and rely on their clinical assessment.

Focus on one thing at a time. After you skim a few related papers on your topic, you should have an idea on what are the main risk factors, complications, or whatever else all the papers make a fuss about. Take a pass through all papers and just focus on this one variable so you develop judgment. You’ll flounder if you try to go through every paper and record every single detail into twenty different columns. You’ll quickly get lost in the minutia. As you’re reading papers, it’s easy to go down rabbit trails with new references you’ve not yet seen; you should put those in a separate list for later.

Data analysis

Simple descriptive statistics (mean, std) can be done in a spreadsheet.

The Cochrane Collaboration provides RevMan for you to produce Forest plots that visually depict the pooled analysis. For the highest quality images, export to EPS and then convert to TIFF if the journal requires that format.

Before you really get too far into things, read the chapter on meta analyses from the Biostat Handbook online. It has a nice illustrative example of garbage-in-garbage-out. In fact, read all of the articles on that site.

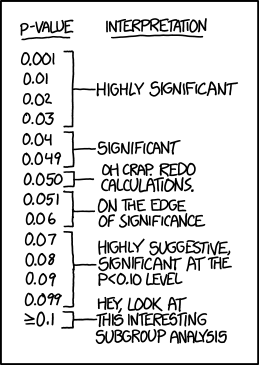

Blinded by significance. As you’re sorting through studies, avoid the urge to only hunt for significant findings. Your job is to report the facts. It may seem sexy to report that some procedure has significant complications, but if your data turns out to show no significance then it’s okay to report that there was no significant difference. It’s okay for your systematic review to simply report that you found no significant results. That’s still a contribution. As you’re gathering data, it’s important you don’t unintentionally start to filter results.

Meta-analysis. While you can rely on RevMan to handle your pooling, you should read about the Mantel-Haenszel method it uses. I highly recommend setting up some toy problems in a spreadsheet so you know each step of calculating your effect measure (odds ratio, risk ratio) or difference measure (mean difference, standard mean difference), confidence intervals, weights, and pooled results along with p-values, Chi2, heterogeneity (I2) (see Higgins 2003). This is important because many times your data is not in a form that RevMan accepts. For example, to pool correlation coefficients (Pearson, Spearman) you have to first z-transform them to a normal distribution so you can get a standard error, run through the MH calculations, and then reverse z-transform to get back to a correlation coefficient.

Random-effects vs fixed-effects models. Try to get a sense of these two and when to use which one. Here’s my best shot at explaining… Fixed-effects is for when you have several consistent studies and you think the real answer is something like a blend of these. Random-effects is for when you have a more heterogeneous set of studies and you think these represent a sampling of all possible studies. Fixed-effects tends to have a tighter confidence interval while random is wider because you’re less sure. In practice, look at your heterogeneity measure (I2) and whether it is significant (Chi2); if significant (p < 0.05) then use random-effects, otherwise use fixed-effects. I’m sure the statisticians in the audience are cringing but this should be enough to get you started. Most universities have some library or department staff available to help you navigate this, or get someone on board who’s done these before.

Writing

Don’t get bogged down. Staring at a blank document can be overwhelming. Where do you start? Start by reading the instructions to authors for your target journal. Lay out the headings it requires.

XXX. As you write, if there’s something you’re unsure how to word or what to cite, put “XXX” and keep going. Come back later. Write whatever you can and move on to the next thing you can write. Over time, the paper will evolve as you hammer out a paragraph here, a paragraph there.

Copy and modify. Look to existing papers for how you can word things or what to mention where. Sometimes when I have writer’s block, I’ll literally type out a paragraph from a paper that says what I want to say; then I will tear that to pieces as I go through and rewrite in my own words using my own findings. I’m not advocating plagiarism here; I’m suggesting you copy sentence and paragraph structure. Whenever you get stuck in your paper, jump over to read a few other papers to see how they handled this particular spot. But don’t go down the rabbit trail of reading for an hour; you can always write “XXX” and come back.

Methods. Write this section first. It should be the most straight forward: you’re just documenting what you did. Look at other papers to see what is important to document and in what order. Follow the PRISMA formula, but don’t get too bogged down with all the details; do as much as you can and move on.

Introduction. Make this brief, like two paragraphs. First paragraph is broad strokes introducing the topic and a few notable works. This is not a discussion; it is merely an introduction of topics. Second paragraph motivates your work: what question are you seeking to answer? You must have a good motivation, not simply “Previous studies suck. I could do better.”

Discussion. Break it into sections for each of the topics. From most studies, you’ll generally only be including information that’s mentioned in the abstract; anything else buried inside a paper is not likely important. For each topic, highlight the papers where that topic was a primary outcome. You don’t need to wring every nugget from each paper; just highlight one takeaway for each. When citing another paper’s finding, don’t include their p-value; that lacks sufficient context. If the reader is interested, they can follow the citation to read the full paper.

Citations. Don’t get caught up in citations; it can distract from your communication. Focus first on saying what you want to say in the order you want to say it; then later integrate citations. In my first pass, I might manually put a citation in parenthesis (Smith), and later worry about fussing with the plugin.