Washington: A Life

Book review: British officer, American general, first president.

George Washington was a British officer, the commanding general in the American Colonial Revolution, reluctant political figure, and by his actions defined the role of President of the United States.

British Officer. Before the revolution, Washington rose to the rank of Major in the colonial branch of the British army. Since he was not part of the core British regiments, he was always treated as a second class soldier and hit a glass ceiling for promotion. His frustration over this likely helped tip him toward revolution.

Discipline and routine. He rose at dawn to survey his land during his days as a farmer or troops as a general.

Several times early in the war he jumped into battle to turn the course of events. This risk to self both worried his generals and inspired his troops. With time, he came to realize the risk to his army if he were to be lost and he relied more on his generals.

Chronic debt. With the war and presidency consuming his attention, his farm crops were chronically unsuccessful and often ran at a loss. On top of that, he liked nice things: shopping sprees whenever he traveled, ordering the latest fashions from Europe. After assuming the presidency, he ceased to purchase from Europe and instead focused one wearing “Made in the USA” clothing to show his support.

Honored his personal debt. Even though many colonists used the successful ending of the revolution as an excuse to not repay debts owed to British, Washington made a point to pay down his personal debts. Unfortunately, hyper-inflation of the colonial currency made it more difficult for him to collect on the debts he was owed by land tenants and such.

Assumed state debt to bind the union. During the revolution, each state went into debt, both domestic and foreign. Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury Secretary, proposed the federal government assume all state debt. Having just thrown off one tyrannical government, many states feared now being indebted to a new master, but ultimately the plan prevailed. The most important effect of pooling debt in this new government was to bind the states into a union under one bank.

Discipline

As president, he lectured a young relative about to enter college that “every hour misspent is lost forever” and that “future years cannot compensate for lost days at this period of your life.”

Corollary: Waste a dollar and you can always later earn a dollar to replace it, but waste an hour and it’s gone forever.

A master of the profitable use of time, Washington listed his monthly doings in his diary under the rubric “Where and how my time is spent.” Whether for business or social occasions, his punctuality was legendary, and he expected everyone to be on time. In his business dealings, he boasted that “no man discharges the demand of wages or fulfills agreements with more punctuality than I do.”

His love of ritual, habit, and order enabled him to sustain the long, involved tasks that distinguished his life. “System in all things is the soul of business,” he liked to say. “To deliberate maturely and execute promptly is the way to conduct it to advantage.”

Washington benefited from the unvarying regularity of his daily routine and found nothing monotonous about it. Like many thrifty farmers, he rose before sunrise and accomplished much work while others still slept. Prior to breakfast, he shuffled about in dressing gown and slippers and passed an hour or two in his library, reading and handling correspondence. He also devoted time to private prayers before Billy Lee laid out his clothes, brushed his hair, and tied it in a queue. Washington liked to examine his stables before breakfast, inspect his horses, and issue instructions to the grooms. Then he had an unchanging breakfast of corn cakes, tea, and honey.

Washington couldn’t bear anything slovenly. “I shall begrudge no reasonable expense that will contribute to the improvement and neatness of my farms, for nothing pleases me better than to see them in good order and everything trim, handsome, and thriving about them,” he advised one estate manager. “Nor nothing hurts me more than to find them otherwise and the tools and implements laying wherever they were last used, exposed to injuries from rain, sun, etc.” No detail was too trivial to escape his notice, and he often spouted the Scottish adage “Many mickles make a muckle”—that is, tiny things add up.

Revolution

If Britain had treated colonists as first class citizens, the revolution might have never have reached critical mass, and America might still be a colony.

Washington’s first stirrings of anti-British fervor had arisen from his failure to receive a royal commission, but they were now joined by disenchantment over pocketbook issues. Great Britain was simply bad for local business, a fact that would soon foster the historical anomaly of a revolution inaugurated by affluent, conservative leaders. As potentates of vast estates, lords of every acre they saw, George Washington and other planters didn’t care to truckle to a distant, unseen power.

I had always pictured the Founding Fathers all being roughly the same age, but of course they were all in different stages of life. Franklin was the elderly grandfatherly figure. Washington was not much younger. Jefferson was just a student.

In the House of Burgesses, a young rabble-rouser, Patrick Henry, rose amid the dark wooden benches and brandished fiery resolutions. “Resolved,” he announced, “that the taxation of the people by themselves or by persons chosen by themselves to represent them . . . is the distinguishing characteristic of British freedom.” For a young law student standing in the rear of the hushed chamber, these words sounded with a thrilling resonance. “He appeared to me to speak as Homer wrote,” Thomas Jefferson remembered.

Washington’s personal debt burden weighted heavily on his shoulders and factored keenly into his thoughts on secession. His insight here into the psychology of debt is as true today as it was then.

On April 5, 1769, Washington sent Mason a remarkable letter that gave both his private and his public reasons for supporting a boycott of British goods. Doubtless thinking of his own plight, he said a boycott would break the onerous cycle of debt that trapped many colonists, purging their extravagant spending. Before this the average colonial debtor was too weak to break this habit, “for how can I, says he, who have lived in such and such a manner, change my method? . . . besides, such an alteration in the system of my living will create suspicions of a decay in my fortune and such a thought the world must not harbor.” Washington provided here a key insight into the psychology of debt: fear that any attempt at a more frugal existence would disclose the truth about a person’s actual wealth.

Declaring an official revolt was dangerous. For these colonists, it was an all or nothing decision. If they failed, they knew what fate awaited them. They risked everything.

The Declaration made the rebels’ treason official and reminded them of the unspeakable punishments the British government meted out for this offense. Only recently a British judge had handed down this grisly sentence to Irish revolutionaries: “You are to be drawn on hurdles to the place of execution, where you are to be hanged by the neck, but not until you are dead, for while you are still living your bodies are to be taken down, your bowels torn out and burned before your faces, your heads then cut off, and your bodies divided each into four quarters.”

The French revolution came soon after the American revolution, but both were founded on very different ideals.

An essential difference between the American and French revolutions was that the American version allowed a search for many truths, while French zealots tried to impose a single sacred truth that allowed no deviation.

Personal

Washington was chronically in debt.

Money was the one area where Washington tended to dodge personal responsibility and blame force majeure.

While public life forced Washington into expenditures beyond his control, during his entire adult life he had exhibited an inability to live within his means.

Throughout the war, Washington was torn between the crumbling colonial army and his crumbling personal property.

Washington must have been distressed by the creeping signs of decay everywhere. Whatever the war’s outcome, he would be left a poorer man, which weighed heavily on his mind. That June, in a letter to William Crawford, the steward of his western lands, he broke down and confided his concern about his wealth withering away as the war progressed: “My whole time is . . . so much engrossed by the public duties of my station that I have totally neglected all my private concerns, which are declining every day, and may possibly end in capital losses, if not absolute ruin, before I am at liberty to look after them.”

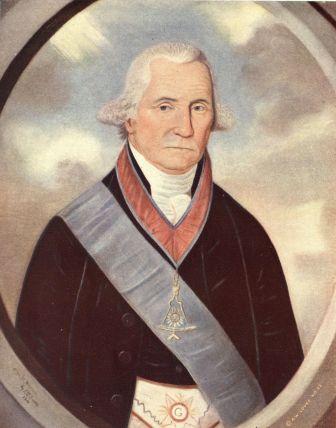

The pastel portrait that Williams executed on September 18, 1794, shows a particularly dour, cranky Washington, with a tightly turned-down mouth. Posing in a black coat, he wears Masonic symbols on a blue sash that slants diagonally across his chest. His face is neither friendly nor heroic but looks like that of a bad-tempered relative, suggesting that the presidency was now a trial he endured only for the public good. Unsparing in its accuracy, the Williams portrait shows various blemishes on Washington’s face—a scar that curves under the pouch of his left eye; a mole below his right earlobe; smallpox scars on both his nose and cheeks—ordinarily edited out of highly sanitized portraits.

Government

Washington presided over a rabble citizenry that just toppled its previous government. Always conscious of its populist tendencies, he tried to shepherd gently.

One virtue of a war that dragged on for so many years was that it gave the patriots a long gestation period in which to work out the rudiments of a federal government, financial mechanisms, diplomatic alliances, and other elements of a modern nation-state.

Try though he might, Washington couldn’t completely extricate his thoughts from politics and feared that the still immature country would blunder into errors before arriving at true wisdom. As he affirmed, “all things will come right at last. But, like a young heir come a little prematurely to a large inheritance, we shall wanton and run riot until we have brought our reputation to the brink of ruin.” Only when a crisis materialized would the country be “compelled perhaps to do what prudence and common policy pointed out as plain as any problem in Euclid in the first instance.” This statement tallied with Washington’s often expressed view that citizens had to feel before they saw—that is, they couldn’t react to abstract problems, only to tangible ones.

The long fight against British tyranny, paradoxically, only strengthened his view that the foremost political danger came not from an overly powerful central government but from an enfeebled one—“a half-starved, limping government that appears to be always moving upon crutches and tottering at every step.”

Shays’s Rebellion crystallized for him the need to overhaul the Articles of Confederation. “What stronger evidence can be given of the want of energy in our governments than these disorders?” he asked Madison. “If there exists not a power to check them, what security has a man of life, liberty, or property?”

He also knew that the American public needed to contribute its share; the Constitution “can only lay the foundation—the community at large must raise the edifice.”

Closer in tone to future inaugural speeches was his ringing expression of faith in the American people. He devised a perfect formulation of popular sovereignty, writing that the Constitution had brought forth “a government of the people: that is to say, a government in which all power is derived from, and at stated periods reverts to, them—and that, in its operation . . . is purely a government of laws made and executed by the fair substitutes of the people alone.”

A whirlwind of energy, Madison would seem omnipresent in the early days of Washington’s administration. He drafted not only the inaugural address but also the official response by Congress and then Washington’s response to Congress, completing the circle.

Although Washington seemed unaware of it, Hamilton had been training for the Treasury post throughout the war, boning up on subjects as diverse as foreign exchange and central banks. Like Washington, Knox, and other Continental Army officers, Hamilton had perceived an urgent need for an active central government, and he grasped the reins of power with a sure-handed gusto that set the tenor for the administration. He headed a Treasury Department that, with thirty-nine employees, instantly surpassed the rest of the government in size. Of particular importance, he presided over an army of customs inspectors whose import duties served as the government’s main revenue source.

In its sparsely worded style, the Constitution mandated that the president, from time to time, should give Congress information about the state of the Union, but it was Washington who turned this amorphous injunction into a formal speech before both houses of Congress, establishing another precedent. Trailing him in his entourage were the chief justice and members of his cabinet, leading to yet another tradition: that the State of the Union speech (then called the annual address) would feature leading figures from all three branches of government. Everything about the new government still had an improvised feel, and Washington’s advent occasioned some last-minute scurrying in the Senate chamber.

Hamilton was also persuaded that, since the debt had been raised to finance a national war, the federal government should assume responsibility for the states’ debts as well. Such an act of “assumption” would have extraordinarily potent political effects, for holders of state debt would transfer their loyalty to the new central government, binding the country together. It would also reinforce the federal government’s claim to future tax revenues in any controversies with the states.

Washington had ten days to sign or veto the bank bill and stalled in making up his mind. Perhaps by design, Hamilton delivered, and Washington accepted, the argument in favor of the bill right before that deadline expired, leaving no time for an appeal inside the cabinet. When Washington signed the bill on February 25, 1791, it was a courageous act, for he defied the legal acumen of Madison, Jefferson, and Randolph. Unlike his fellow planters, who tended to regard banks and stock exchanges as sinister devices, Washington grasped the need for these instruments of modern finance. It was also a decisive moment legally for Washington, who had felt more bound than Hamilton by the literal words of the Constitution. With this stroke, he endorsed an expansive view of the presidency and made the Constitution a living, open-ended document. The importance of his decision is hard to overstate, for had Washington rigidly adhered to the letter of the Constitution, the federal government might have been stillborn. Chief Justice John Marshall later seized upon the doctrine of “implied powers” and incorporated it into seminal Supreme Court cases that upheld the power of the federal government.

Washington and other founders entertained the fanciful hope that America would be spared the bane of political parties, which they called “factions” and associated with parochial self-interest. The first president did not see that parties might someday clarify choices for the electorate, organize opinion, and enlist people in the political process; rather he feared that parties could blight a still fragile republic. He was hardly alone. “If I could not go to heaven but with a party,” Jefferson opined, “I would not go there at all.” Yet the first factions arose from Jefferson’s extreme displeasure with Hamilton’s mounting influence. They were not political parties in the modern sense so much as clashing coteries of intellectual elites, who operated through letters and conversations instead of meetings, platforms, and conventions. Nonetheless these groups solidified into parties during the decade and, notwithstanding the founders’ fears, formed an enduring cornerstone of American democratic politics.

However trying he often found the press, Washington understood its importance in a democracy and voraciously devoured gazettes. Before becoming president, he had lauded newspapers and magazines as “easy vehicles of knowledge, more happily calculated than any other to preserve the liberty . . . and meliorate the morals of an enlightened and free people.” In his unused first inaugural address, he had gone so far as to advocate free postal service for periodicals. As press criticism mounted, however, Washington struggled to retain his faith in an independent press. In October 1792 he told Gouverneur Morris that he regretted that newspapers exaggerated political discontent in the country, but added that “this kind of representation is an evil w[hi]ch must be placed in opposition to the infinite benefits resulting from a free press.” A month later, in a more somber mood, he warned Jefferson that Freneau’s invective would yield pernicious results: “These articles tend to produce a separation of the Union, the most dreadful of calamities; and whatever tends to produce anarchy, tends, of course, to produce a resort to monarchical government.”

At the end he struck a note of serenity, a faith that the American experiment, if sometimes threatened, would prevail. While fearful of machinations, he told Trumbull, “I trust . . . that the good sense of our countrymen will guard the public weal against this and every other innovation and that, altho[ugh] we may be a little wrong now and then, we shall return to the right path with more avidity.” 15 It was an accurate forecast of American history, both its tragic lapses and its miraculous redemptions.

The presidential legacy he left behind in Philadelphia was a towering one. As Gordon Wood has observed, “The presidency is the powerful office it is in large part because of Washington’s initial behavior.” Washington had forged the executive branch of the federal government, appointed outstanding department heads, and set a benchmark for fairness, efficiency, and integrity that future administrations would aspire to match. “A new government, constructed on free principles, is always weak and must stand in need of the props of a firm and good administration till time shall have rendered its authority venerable and fortified it by habits of obedience,” Hamilton wrote. Washington had endowed the country with exactly such a firm and good administration, guaranteeing the survival of the Constitution. He had taken the new national charter and converted it into a viable, elastic document. In a wide variety of areas, from inaugural addresses to presidential protocol to executive privilege, he had set a host of precedents that endured because of the high quality and honesty of his decisions. Washington’s catalog of accomplishments was simply breathtaking. He had restored American credit and assumed state debt; created a bank, a mint, a coast guard, a customs service, and a diplomatic corps; introduced the first accounting, tax, and budgetary procedures; maintained peace at home and abroad; inaugurated a navy, bolstered the army, and shored up coastal defenses and infrastructure; proved that the country could regulate commerce and negotiate binding treaties; protected frontier settlers, subdued Indian uprisings, and established law and order amid rebellion, scrupulously adhering all the while to the letter of the Constitution. During his successful presidency, exports had soared, shipping had boomed, and state taxes had declined dramatically. Washington had also opened the Mississippi to commerce, negotiated treaties with the Barbary states, and forced the British to evacuate their northwestern forts. Most of all he had shown a disbelieving world that republican government could prosper without being spineless or disorderly or reverting to authoritarian rule. In surrendering the presidency after two terms and overseeing a smooth transition of power, Washington had demonstrated that the president was merely the servant of the people.

The political climate of the day was acrimonious and this was a constant scourge on Washington. As time went on, his early confidants Jefferson and Madison turned on him. Political parties sprang up and discourse was often vitriolic:

Washington never achieved the national unity he desired and, by the end, presided over a deeply riven country. John Adams made a telling point when he later noted that Washington, an apostle of unity, “had unanimous votes as president, but the two houses of Congress and the great body of the people were more equally divided under him than they ever have been since.” This may have been unavoidable as the new government implemented the new Constitution, which provoked deep splits over its meaning and the country’s future direction. But whatever his chagrin about the partisan strife, Washington never sought to suppress debate or clamp down on his shrill opponents in the press who had hounded him mercilessly. To his everlasting credit, he showed that the American political system could manage tensions without abridging civil liberties. His most flagrant failings remained those of the country as a whole—the inability to deal forthrightly with the injustice of slavery or to figure out an equitable solution in the ongoing clashes with Native Americans.

Martha

The Presidency clearly took its toll on Washington and his family, as I’m sure every Presidency since then has.

To the end of her life, Martha Washington would speak forlornly of the presidential years as her “lost days.”

Martha Washington had sacrificed so much privacy during her married life that after her husband died, she evened the score by burning their personal correspondence—to the everlasting chagrin of historians.

Leadership

Whether on the plantation, in the army, or in government, he stressed the need to inspire respect rather than affection in subordinates, a common thread running through his vastly disparate managerial activities.

When General Howe herded 300 destitute Bostonians, riddled with disease, onto boats and dumped them near American lines, Washington feared that they carried smallpox; he sent them humanitarian provisions while carefully insulating them from his troops. After a second wave of 150 sickly Bostonians was expelled, Washington grew convinced that Howe had stooped to using smallpox as a “weapon of defense” against his army. By January 1777 he ordered Dr. William Shippen to inoculate every soldier who had never had the disease. “Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure,” he wrote, “for should the disorder infect the army in the natural way and rage with its usual virulence, we should have more to dread from it than the sword of the enemy.” This enlightened decision was as important as any military measure Washington adopted during the war.

Washington tried to rouse his untried men with impassioned words. He had a genius for exalting the mission of his army and enabling the men to see themselves, not as lowly grunts, but as actors on the stage of history. “The time is now near at hand which must probably determine whether Americans are to be free men or slaves . . . The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage . . . of this army.”

Finally he was stranded alone on the battlefield with his aides, his troops having fled in fright. Most astonishingly, Washington on horseback stared frozen as fifty British soldiers started to dash toward him from eighty yards away. Seeing his strangely catatonic state, his aides rode up beside him, grabbed the reins of his horse, and hustled him out of danger. In this bizarre conduct, Nathanael Greene saw a suicidal impulse, contending that Washington was “so vexed at the infamous conduct of his troops that he sought death rather than life.” Weedon added the compelling detail that only with difficulty did Washington’s colleagues “get him to quit the field, so great was his emotions.” It was a moment unlike any other in Washington’s career, a fleeting emotional breakdown amid battle.

He seemed to know implicitly that no loyalty surpassed that of a man forgiven for his faults who vowed never to make them again.

Yet despite the calamities at Forts Washington and Lee, the British had done Washington an inadvertent favor. They had shown him the futility of trying to defend heavily fortified positions along the seaboard and forced him out into the countryside, where he had mobility and where the British Army, deprived of the Royal Navy, operated at a disadvantage. For political reasons, Washington hadn’t been able to countermand the congressional decision to defend New York City and the Hudson River, but now that he had done so and suffered predictable defeats, he would have more freedom to pick and choose his targets. With his drastically diminished army and depleted supplies, it was no longer a question of standing and confronting the British with their vastly superior troops and firepower.

English poet Edward Young: “ ‘Affliction is the good man’s shining time.’”

Washington demanded self-sacrifice from aides, who had to follow his schedule uncomplainingly. If he slept in the open air before a battle, so did they. “When I joined His Excellency’s suite,” wrote James McHenry, “I gave up soft beds, undisturbed repose, and the habits of ease and indulgence . . . for a single blanket, the hard floor or the softer sod of the fields, early rising, and almost perpetual duty.”

Washington was adept at identifying young talent. He wanted eager young men who worked well together, pitched in with alacrity, and showed esprit de corps. His own personality forbade backslapping familiarity or easy joviality. Beneath his reserve, however, he had an excellent capacity for reading people and adapting his personality to them. As before the war, he remained wary in relationships and lowered his emotional barriers only slowly, but he was trusting once colleagues earned his confidence.

Since the Battle of Monmouth, Washington had soldiered on for more than two years without a major battle, and Lafayette told him of impatience at Versailles with his supposed passivity. Washington replied that this inactivity was involuntary: “It is impossible, my dear Marquis, to desire more ardently than I do to terminate the campaign by some happy stroke, but we must consult our means rather than our wishes.”

Washington surrounded himself with a small but decidedly stellar group. With his own renown secure, he had no fear that subordinates would upstage him and never wanted subservient courtiers whom he could overshadow. Aware of his defective education, he felt secure in having the best minds at his disposal. He excelled as a leader precisely because he was able to choose and orchestrate bright, strong personalities. As Gouverneur Morris observed, Washington knew “how best to use the rays” given off by the sparkling geniuses at his command. 9 As the first president, Washington assembled a group of luminaries without equal in American history; his first cabinet more than made up in intellectual fire-power what it lacked in numbers.

Washington’s accomplishments as president were no less groundbreaking than his deeds in the Continental Army. It is a grave error to think of George Washington as a noble figurehead presiding over a group of prima donnas who performed the real work of government. As a former commander in chief, he was accustomed to a chain of command and delegating important duties, but he was also accustomed to having the final say. As president, he enjoyed unparalleled power without being autocratic. He set out less to implement a revolutionary agenda than to construct a sturdy, well-run government, and in the process he performed many revolutionary acts.

Washington grew as a leader because he engaged in searching self-criticism. “I can bear to hear of imputed or real errors,” he once wrote. “The man who wishes to stand well in the opinion of others must do this, because he is thereby enabled to correct his faults or remove prejudices which are imbibed against him.” The one thing Washington could not abide was when people published criticisms of him without first giving him a chance to respond privately.

Henry Knox was one of his most trusted generals, until Knox chose his family over the war efforts. Washington may have begrudged him, because he himself was constantly submitting his personal affairs to those of the nation:

While Washington was at Carlisle, Henry Knox belatedly returned to Philadelphia. It must have dawned on him just how annoyed Washington was by his protracted absence, for he sent him a letter awash with “inexpressible regret that an extraordinary course of contrary winds” had delayed his return. Knox volunteered to join Washington at Carlisle and must have been shocked by his curt reply: “It would have given me pleasure to have had you with me on my present tour and advantages might have resulted from it, if your return in time would have allowed it. It is now too late.” This was a remarkable message: the president was banishing the secretary of war from the largest military operation to unfold since the Revolutionary War. In addition to giving Knox a stinging rap on the knuckles, Washington must also have seen that Hamilton had assumed a commanding posture and would have yielded to Knox only with reluctance.

[H]e summed up his executive style: “Much was to be done by prudence, much by conciliation, much by firmness.”

Hamilton nicely sums up Washington’s approach to major decisions:

Hamilton concurred that the president “consulted much, pondered much; resolved slowly, resolved surely.”

Well aware of his own executive style, Washington once instructed a cabinet member “to deliberate maturely, but to execute promptly and vigorously.”

Washington once advised his adopted grandson that “where there is no occasion for expressing an opinion, it is best to be silent, for there is nothing more certain than that it is at all times more easy to make enemies than friends.”

A taciturn man, Washington never issued opinions promiscuously. A disciplined politician, he never had to retract things uttered in a thoughtless moment. “Never be agitated by more than a decent warmth and offer your sentiments with modest diffidence,” he told his nephew Bushrod, noting that “opinions thus given are listened to with more attention than when delivered in a dictatorial style.” He worried about committing an error more than missing a brilliant stroke. Washington also hated boasting.

By the time of his death, Washington had poured his last ounce of passion into the creation of his country. Never a perfect man, he always had a normal quota of human frailty, including a craving for money, status, and fame. Ambitious and self-promoting in his formative years, he had remained a tightfisted, sharp-elbowed businessman and a hard-driving slave master. But over the years, this man of deep emotions and strong opinions had learned to subordinate his personal dreams and aspirations to the service of a larger cause, evolving into a statesman with a prodigious mastery of political skills and an unwavering sense of America’s future greatness. In the things that mattered most for his country, he had shown himself capable of constant growth and self-improvement. George Washington possessed the gift of inspired simplicity, a clarity and purity of vision that never failed him. Whatever petty partisan disputes swirled around him, he kept his eyes fixed on the transcendent goals that motivated his quest. As sensitive to criticism as any other man, he never allowed personal attacks or threats to distract him, following an inner compass that charted the way ahead. For a quarter century, he had stuck to an undeviating path that led straight to the creation of an independent republic, the enactment of the Constitution, and the formation of the federal government. History records few examples of a leader who so earnestly wanted to do the right thing, not just for himself but for his country. Avoiding moral shortcuts, he consistently upheld such high ethical standards that he seemed larger than any other figure on the political scene. Again and again the American people had entrusted him with power, secure in the knowledge that he would exercise it fairly and ably and surrender it when his term of office was up. He had shown that the president and commander in chief of a republic could possess a grandeur surpassing that of all the crowned heads of Europe. He brought maturity, sobriety, judgment, and integrity to a political experiment that could easily have grown giddy with its own vaunted success, and he avoided the backbiting, envy, and intrigue that detracted from the achievements of other founders. He had indeed been the indispensable man of the American Revolution.

Anti-slavery

Whatever his motivations, it was a water-shed moment in American history, opening the way for approximately five thousand blacks to serve in the Continental Army, making it the most integrated American fighting force before the Vietnam War. At various times, blacks would make up anywhere from 6 to 12 percent of Washington’s army.

That winter the projected shortage of soldiers led Washington to introduce another significant change in policy. In January 1778 Brigadier General James Mitchell Varnum of Rhode Island asked the unthinkable of the Virginia planter: the right to augment his state’s forces by recruiting black troops. “It is imagined that a battalion of Negroes can be easily raised there,” he assured Washington. Washington knew this was an incendiary idea for many southerners. Nevertheless, desperate to recruit more manpower, he gave his stamp of approval, telling Rhode Island’s governor “that you will give the officers employed in this business all the assistance in your power.” The state promised to free any slaves willing to join an all-black battalion that soon numbered 130 men. Massachusetts followed Rhode Island’s lead in enlisting black soldiers, and in Connecticut, slave masters were exempt from military service if they sent slaves in their stead. That August a census listed 755 blacks as part of the Continental Army, or nearly 5 percent of the total force.

By freeing his slaves, Washington accomplished something more glorious than any battlefield victory as a general or legislative act as a president. He did what no other founding father dared to do, although all proclaimed a theoretical revulsion at slavery. He brought the American experience that much closer to the ideals of the American Revolution and brought his own behavior in line with his troubled conscience.

Governance

In early January, amid rumors of mass resignations, a three-man delegation of officers went to Philadelphia to lay before Congress a petition that catalogued their pent-up grievances: “We have borne all that men can bear—our property is expended—our private resources are at an end.” This delegation met with two dynamic young members of Congress: James Madison of Virginia, a member since 1780, and Alexander Hamilton of New York, who had joined Congress a little more than a month earlier. However alarmed by the prospect of an officer mutiny, Hamilton believed it might represent a handy lever with which to budge a lethargic Congress from inaction, leading to expanded federal powers. On February 13 Hamilton wrote to Washington in a candid tone that presupposed that a profound understanding still existed between them. He talked of the critical state of American finances and suggested that the officer revolt could be helpful: “The claims of the army, urged with moderation but with firmness, may operate on those weak minds which are influenced by their apprehensions rather than their judgment . . . But the difficulty will be to keep a complaining and suffering army within the bounds of moderation.” In suggesting that Washington exploit the situation to influence Congress, Hamilton toyed with combustible chemicals. He also tried to awaken anxiety in Washington by telling him that officers were whispering that he didn’t stand up for their rights with sufficient zeal. “The falsehood of this opinion no one can be better acquainted with than myself,” Hamilton emphasized, “but it is not the less mischievous for being false.” On March 4 Washington sent Hamilton a thoughtful response and disclosed grave premonitions about the crisis. “It has been the subject of many contemplative hours,” he told Hamilton. “The sufferings of a complaining army, on one hand, and the inability of Congress and tardiness of the states on the other, are the forebodings of evil.” He voiced concern at America’s financial plight and told of his periodic frustration at being excluded from congressional decisions. If Congress didn’t receive enlarged powers, he maintained, revolutionary blood would have been spilled in vain. After spelling out areas of agreement with Hamilton, however, Washington said he refused to deviate from the “steady line of conduct” he had pursued and insisted that the “sensible and discerning” officers would listen to reason. He also asserted that any attempt to exploit officer discontent might only “excite jealousy and bring on its concomitants.” It was a noble letter: Washington refused to pander to any political agenda, even one he agreed with, and he would never encroach upon the civilian prerogatives of Congress. In a later letter Washington was even blunter with Hamilton, warning him that soldiers weren’t “mere puppets” and that the army was “a dangerous instrument to play with.” The officers continued to believe that Philadelphia politicians remained deaf to their pleas, and Washington had no inkling that they would soon resort to more muscular measures. In his general orders for March 10, he dwelt on a mundane topic, the need for uniform haircuts among the troops. Then he learned of an anonymous paper percolating through the camp, summoning officers to a mass meeting the next day to air their grievances—a brazen affront to Washington’s authority and, to his mind, little short of outright mutiny. Then a second paper made the rounds, further stoking a sense of injustice. Its anonymous author was, in all likelihood, John Armstrong, Jr., an aide-de-camp to Horatio Gates, who mocked the peaceful petitions drawn up by the officers and warned that, come peace, they might “grow old in poverty, wretchedness, and contempt.” Before being stripped of their weapons by an armistice, they should now take direct action: “Change the milk and water style of your last memorial—assume a bolder tone . . . And suspect the man who would advise to more moderation and…

On political parties:

While he acknowledged their right to protest, he was persuaded that the new societies constituted a menace because their permanence > showed a settled hostility to the government.

Foreign Policy

His skepticism about French motives would harden into a corner-stone of his foreign policy. His fellow citizens, he thought, were too ready to glorify France, which had entered the war to damage Britain, not to aid the Americans. “Men are very apt to run into extremes,” he warned Henry Laurens. “Hatred to England may carry some into an excess of confidence in France, especially when motives of gratitude are thrown into the scale.” John Adams summed up the situation memorably when he said that the French foreign minister kept “his hand under our chin to prevent us from drowning, but not to lift our heads out of water.” In yet another sign of his growing political acumen, Washington generalized this perception into an enduring truth of foreign policy, noting that “it is a maxim founded on the universal experience of mankind that no nation is to be trusted farther than it is bound by its interest.”

Because the states had refused to collect their quota of taxes, Morris couldn’t service the sizable debt raised to finance the war. He warned that creditors “who trusted us in the hour of distress are defrauded” and that it was pure “madness” to “expect that foreigners will trust a government which has no credit with its own citizens.”

While Washington grew increasingly apprehensive about the violent events in Paris, Jefferson viewed them with philosophical serenity, lecturing Lafayette that one couldn’t travel “from despotism to liberty in a feather-bed.”

In August 1792, to Lafayette’s horror, the Jacobins incited a popular insurrection that included the storming of the Tuileries in Paris and the butchery of the Swiss Guards defending the palace. The king was abruptly dethroned. Refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to the civil constitution, nearly 25,000 priests fled the country amid a horrifying wave of anticlerical violence. A month later Parisian mobs engineered the September Massacres, slaughtering more than fourteen hundred prisoners, many of them aristocrats or royalist priests. Ejected from his military command and charged with treason, Lafayette fled to Belgium. “What safety is there in a country where Robespierre is a sage, Danton is an honest man, and Marat a God?” he wondered. Arrested by Austrian forces, he spent the next five years languishing in ghastly Prussian and Austrian prisons. With cruel irony, he was charged with having clapped the French king in irons and kept him in captivity. While claiming the rights of an honorary American citizen, Lafayette was confined in a small, filthy, vermin-infested cell.

On January 21, 1793, the former King Louis XVI, who had helped win American independence, was decapitated before a crowd of twenty thousand people intoxicated with a lust for revenge. After stuffing the king’s head between his legs, the executioner flung his remains into a rude cart piled with corpses, while bystanders dipped souvenirs into the royal blood pooled under the guillotine. Vendors soon hawked patches of the king’s clothing and locks of bloodstained hair, in a spectacle of sadistic glee that shocked many people inside and outside France. On February 1 France declared war on Great Britain and Holland.

On the Jay Treaty: “As it happened, four days later the document sat on his desk. Washington must have quietly gagged as he pored over its provisions, which seemed heavily slanted toward Great Britain. The treaty failed to stem the odious British practice of seizing American sailors on the high seas. Shockingly, it granted British imports most-favored-nation status, even though England did not reciprocate for American imports. Once the treaty was revealed, it would seem to many as if Jay had groveled before his British counterparts in a demeaning throwback to colonial times. The treaty would strike southerners as further damning proof that Washington was a traitor to his heritage, for Jay had failed to win compensation for American slaves carted off at the end of the war. For all that, the treaty had several redeeming features. England finally consented to evacuate the forts on the Great Lakes; it opened the British West Indies to small American ships; and it agreed to compensate American merchants whose freight had been confiscated. And these concessions paled in comparison to the treaty’s overriding achievement: it arrested the fatal drift toward war with England. On balance, despite misgivings, Washington thought the flawed treaty the best one feasible at the moment.

The uproar was overwhelming, tagging Jay as the chief monster in the Republicans’ bestiary. In the treaty, Republicans saw a blatant partiality for England and equally barefaced hostility toward France. Critics gave way to full-blown paranoid fantasies that Jay, in the pay of British gold, had suborned other politicians to introduce a monarchical cabal. Some protests bordered on the obscene, especially a bawdy poem in the Republican press about Jay’s servility to the British king: “May it please your highness, I John Jay / Have traveled all this mighty way, / To inquire if you, good Lord, will please, / to suffer me while on my knees, / to show all others I surpass / In love, by kissing of your———.” 5 By the July Fourth celebrations, Jay had been burned in effigy in so many towns that he declared he could have traversed the entire country by the glare of his own flaming figure.

Tacitly railing against Republican support for France, he expounded a foreign policy based on practical interests instead of political passions: “The nation which indulges towards another an habitual hatred, or an habitual fondness, is in some degree a slave.” Sympathy with a foreign nation for purely ideological reasons, he said, could lead America into “the quarrels and wars of the latter without adequate inducement or justification.” He clearly had Jefferson and Madison in mind as he took issue with “ambitious, corrupted or deluded citizens (who devote themselves to the favorite nation)” and “sacrifice the interests of their own country.” Restating his neutrality policy, he underlined the desirability of commercial rather than political ties with other nations: “ ‘Tis our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” It was Jefferson, not Washington, who warned against “entangling alliances,” although the concept was clearly present in Washington’s message.

Behavior

While Washington cultivated friendships throughout his life, he didn’t have many true intimates and his relationships were seldom of the candid or confessional type. His reserve, if not impenetrable, was by no means lightly surrendered. He was habitually cautious with new people and only gradually opened up as they passed a series of loyalty tests. “Be courteous to all but intimate with few,” he advised his nephew, “and let those few be well tried before you give them your confidence. True friendship is a plant of slow growth.”

In trying to form himself as an English country gentleman, the self-invented young Washington practiced the classic strategy of outsiders: he studied closely his social betters and tried to imitate their behavior in polite society. Whether to improve his penmanship or perhaps as a school assignment, he submitted to the drudgery of copying out 110 social maxims from The Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation,

Washington believed that ambitious men should hide their true selves, retreat into silence, and not tip people off to their ambition. To sound out people, you had to feign indifference and proceed only when convinced that they were sympathetic and like-minded. The objective was to learn the maximum about other people’s thoughts while revealing the minimum about your own. Always fearful of failure, Washington wanted to push ahead only if he was armed with detailed knowledge and enjoyed a high likelihood of success. This cautious, disciplined political style would persist long after the original insecurity that had prompted it had disappeared.

The taciturn Washington wasn’t the kind of glib burgess who sprang to his feet and orated extemporaneously. He practiced a minimalist art in politics, learning how to exert maximum leverage with the least force. Thomas Jefferson, who was to serve with Washington and Franklin in the Continental Congress, spotted their economical approach to power. “I never heard either of them speak ten minutes at a time, nor to any but the main point,” he later said of the two statesmen. “They laid their shoulders to the great points, knowing that the little ones would follow of themselves.” Later on Washington coached his stepson on how to be a Virginia legislator, reminding him to be punctual in attendance and “hear dispassionately and determine coolly all great questions.”

Relationship with his mother Mary Washington

There would always be a cool, quiet antagonism between Washington and his mother. The hypercritical mother produced a son who was overly sensitive to criticism and suffered from a lifelong need for approval. One suspects that, in dealing with this querulous woman, George became an overly controlled personality and learned to master his temper and curb his tongue.

In modern psych, Washington’s mother had histrionic personality disorder. Everything was always about her and she was always acting out to get the attention and sympathy of others.

As best we can tell, Mary Ball Washington boycotted the wedding and, according to Martha’s biographer Patricia Brady, may not have met the bride until the year after the wedding.

Not happy that little George had another lady in his life.

Was Washington a Christian?

If he was, then he didn’t make that clear in the least. He seems more like a deist.

A stalwart member of two congregations, Washington attended church throughout his life and devoted substantial time to church activities. His major rites of passage—baptism, marriage, burial—all took place within the fold of the church. What has mystified posterity and puzzled some of his contemporaries was that Washington’s church attendance was irregular; that he recited prayers standing instead of kneeling; that, unlike Martha, he never took communion; and that he almost never referred to Jesus Christ, preferring such vague locutions as “Providence,” “Destiny,” the “Author of our Being,” or simply “Heaven.” Outwardly at least, his Christianity seemed rational, shorn of mysteries and miracles, and nowhere did he directly affirm the divinity of Jesus Christ.

Numerous historians, viewing Washington as imbued with the spirit of the Enlightenment, have portrayed him as a deist. Eighteenth-century deists thought of God as a “prime mover” who had created the universe, then left it to its own devices, much as a watchmaker wound up a clock and walked away. God had established immutable laws of nature that could be fathomed by human reason instead of revelation. Washington never conformed to such deism, however, for he resided in a universe saturated with religious meaning. Even if his God was impersonal, with scant interest in individual salvation, He seemed to evince a keen interest in North American politics. Indeed, in Washington’s view, He hovered over many battlefields in the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War.

Random

When the British surrendered New York City back to the Americans, one anonymous British officer was still gathering his belongings after the British had departed, and he noted that the Americans were peacefully reentering the city compared to the relatively less peaceful camp-life during the British occupation. He noted:

The Americans are a curious, original people. They know how to govern themselves, but nobody else can govern them.

Unable to tell a lie, Washington admitted in his diary that he had “cut down the two cherry trees in the courtyard.”

That’s where that saying comes from. This was from his own courtyard once the Mount Vernon property was his; not when he was a child.

In addition to his better-known title of Father of His Country, Washington is also revered in certain circles as the Father of the American Mule.

Washington always sought to experiment in better agricultural methods and more hardy livestock.

On Thomas Jefferson’s often duplicitous actions:

The letter gave the world a peek into a very different Thomas Jefferson: not the political savant but the crafty, partisan operative marked by unrelenting zeal.

Prior to leaving New York, Washington also signed a proclamation for the first Thanksgiving on November 26, declaring that “Almighty God” should be thanked for the abundant blessings bestowed on the American people, including victory in the war against England, creation of the Constitution, establishment of the new government, and the “tranquillity, union, and plenty” that the country now enjoyed.

While Washington set the date for one of the first Thanksgiving celebrations, it was not until Lincoln that it became an official federal holiday.

Joined at last by Dr. Brown, they took two more pints from Washington’s depleted body. It has been estimated that Washington surrendered five pints of blood altogether, or about half of his body’s total supply.

Washington would have died either way from his upper respiratory infection, but the multiple rounds of blood letting sure hastened things.